A delegation from the Imam Mahdi Association of North America (I.M.A.M.) led by its Chairman,…

Building Religious Centers for Future Generations

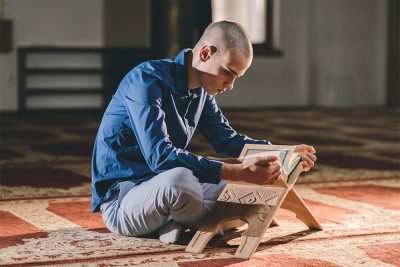

Many of the first Muslim immigrants who came to North America in the 70s and 80s came for higher education anticipating that they would return to their countries to find good work. Over the years, some of them stayed longer than anticipated because they found well-paying jobs and a suitable environment to raise a family. Perhaps some of these first immigrants did not see themselves residing in North America permanently, but over time they became more invested in their new country, and the appeal of returning to their places of origin decreased.

Many of the first Muslim immigrants who came to North America in the 70s and 80s came for higher education anticipating that they would return to their countries to find good work. Over the years, some of them stayed longer than anticipated because they found well-paying jobs and a suitable environment to raise a family. Perhaps some of these first immigrants did not see themselves residing in North America permanently, but over time they became more invested in their new country, and the appeal of returning to their places of origin decreased.

When these immigrants arrived, many of them wanted to preserve and carry on their values and beliefs as a way of staying true to God and fulfilling their obligation of raising a righteous family. They founded places of worship that would not only help fulfill their obligations but also remind them of the environments in which they grew up. Considering their original intentions upon arriving in North America, they may have thought that re-adjustment to life in their native homeland, where they would return one day, would be much easier if they continued to express their faith in the way their old culture used to. This practice remained the bedrock of Muslim immigrant communities in the West such that most mosques and Islamic centers automatically adopted the culture of its majority congregants. Although many first-generation immigrant Muslims have chosen to remain and raise families in North America, these cultural practices have persisted in our places of worship. Yet, these practices are from a different land and time, and under these circumstances result in a deficit of ways to properly support future generations.

For culture to survive and sustain itself, it generally needs a common language and geographic location. But since the geographic location has changed, and the language is not the one spoken widely in society, the culture will only last for a generation or two. Unfortunately, the outcome of a persisting native culture in some places of worship in the West has been the disconnect of the young members of the community. Previously, this caused many centers to bolster their efforts to keep cultural practices alive so that future generations remained connected to their ancestry. In many cases, however, if one looks closely, one can clearly see that these efforts were the result of the older generation’s nostalgia and longing for their native homeland.

Imam Ali (p) said: “Do not force your children to conform to your mannerisms, for surely they are created for a time which is different than your time.”

As a community, many of us have spent an immense amount of time and effort to build places of worship that remind us of our past, rather than prepare our children for their future. If we continue down this path and do not heed the advice of our Imam (p), we may risk having our future generations lose their religion altogether.

Developing North American Shi’ism

As followers of the Ahl al-Bayt (pbut), our faith and devotion cause us to revere and commemorate them. When describing the supporters of the Ahl al-Bayt (pbut), Imam Ali (p) said, “They rejoice in our joy, [and] grieve for our sorrow.” We continue to rekindle these commemorations through the most natural means that many cultures use to express these feelings: poetry. Poetry is a unique form of expression distinctly tied to the essence of the culture that created it. This is evident in the many countries and cultures that have venerated the Ahl al-Bayt (pbut). Each developed their own poetic expressions unique to their respective traditions, historical experiences, and social mores. As such, the immigrants who chose to adopt a foreign land as their home also carried their culture with them and have been trying to impart it to their children to keep the remembrance of the Ahl al-Bayt (pbut) alive. But the question arises, is it the specific cultural method that is important to keep alive or the actual remembrance of the Ahl al-Bayt (pbut)?

When Imam Ali (p) admonishes us not to ‘force’ our children to conform to our mannerisms, he is teaching us to increase our awareness of our environment and adapt to it, while keeping true to our Islamic beliefs and practices, so that we do not lose our future generations. Each of the countries that many Muslim immigrants came from have their own distinct method of remembering the Ahl al-Bayt (pbut), even though they all venerate the same Holy Household (pbut). The Iraqis revere differently than the Lebanese, who commemorate differently than the Iranians, who lament differently than the Afghans, who pay tribute differently than the Pakistanis, who honor differently than the Indians, and so on. Just as our original homelands had their distinct methods of remembering the Ahl al-Bayt (pbut), so too should our North American homeland. It is our responsibility as a community to safeguard the remembrance of the Ahl al-Bayt (pbut) so that it honors them, rather than disgraces them if the practices fall outside of Islamic beliefs and values. For one thing is certain, a new culture of North American Shi’ism will develop eventually on its own as generation after generation grows up in North America. If we work together as a greater community to support these generations in remembering the Ahl al-Bayt (pbut) through the poetry and reverence of their North American culture, we can help ensure their foothold in the path of the Prophet (pbuh&hp) for generations to come. But if we exclude them from our gatherings by not adapting to the culture of our new homeland and by isolating our centers by solely holding on to the cultures of our past, we will not fulfill our responsibility to guide future generations on the proper path. What may develop instead are practices that could possibly, God forbid, bring us shame if they fall outside of Islamic beliefs and values.

Steps to Take

Start to raise awareness among your community members concerning the need to develop an effective environment for future generations, one in which they can participate in expressing their devotion to the Ahl al-Bayt (pbut) through the culture and mannerisms of their time. Work with your community to hold a town hall discussion, which puts the youth front and center, to plan and implement steps for this inclusive environment. Find ways to take on responsibility for the change, and use positive methods to hold each other accountable for the change.

When inviting speakers, remind them of the advice of the Supreme Religious Authority on how “speakers must address the changing customs in every society and in every period to preserve the sanctity and true ethos of the Hussaini movement. This is important because keeping up with new thoughts, trends, and cultural changes draws people towards the pulpit of Imam Hussain (p) with greater impact and effectiveness.” We must also recognize that this advice applies to all speeches throughout the year.

Lastly, and perhaps most importantly, we must continue adopting English as the primary language in our centers. Our youth need to express and explain their faith when their peers ask about Islam, and we should expect that they not have to struggle to translate or interpret these spiritual concepts from a language they do not use regularly. Rather, we should equip them with the proper terms and explanations in our society’s common language so that they will not just concisely explain their faith, but rather make a profound impression on those around them. It is only then that they can preserve the remembrance of the Ahl al-Bayt (pbut) for their generation and the generations to come in our North American homeland.

[1] Bihar al-anwar, vol. 104, p. 99.

[2] Sheikh al-Sadooq, Kitab al-khisal, p. 635.

Related Posts

- I.M.A.M. Delegation Visits Islamic Centers in Georgia

- The Religious Responsibility to Abide by the Laws of One’s Home Country

A common misconception in contemporary society is that Islamic laws are at odds with the…

- Advice of the Supreme Religious Authority to the preachers and public speakers in the month of Muharram

Guidance and advice to all the public speakers and preachers who ascend the pulpit of…

Leave a Comment:

You must be logged in to post a comment.